Rude Girl

on trying to get Maya a British passport

“What is your father’s name?” asks the helpful man with the Liverpool accent. I’m on the phone with His Majesty’s Passport office again, trying to get Maya a British passport.

“It must be hard to try so hard to make something happen and then nothing comes of it,” Stevie said the other night while I was washing my feet in Maya’s bath. He was trying to be helpful, but all I heard was: you’re a failure.

I have spent over seven months in a bureaucracy k-hole. I did everything they asked. I ordered, gathered, and sent birth and wedding certificates for all four of her grandparents. I got an old friend in the UK to confirm Maya’s identity. When asked, I sent my father’s UK passport. HM Passport Office lost his passport and withdrew and closed Maya’s passport application because too much time had passed. I called USPS and they told me I needed to call the UK postal service because the mistake was made across the pond. I called Parcelforce and talked to a very empathetic man who couldn’t believe what I’d been through. I was told my package was signed for at HM Passport Office by someone called MR. TACKYI.

“My dad’s name is Nicholas Archibald Bogle,” I say to the helpful man with the Liverpool accent. I hear him typing.

“Ah yeah, we have his passport. It just wasn’t filed under your application.” My mouth hits the floor. Because of this missing passport, I have opened a missing package claim, talked to a very thorough sounding detective at USPS, and told my dad to cancel it and order a new one.

“It’s funny that no one thought to check his name in the system,” the helpful man says.

“Oh wow, yeah. That is funny,” I say, shaking with fury.

“King Charles should be ashamed to have this passport office named after him,” I tell Stevie as I hang up.

The whole process has been like this. It’s not enough that I’m a British citizen who was born in London, because they took away birthright citizenship in 1981 (what Trump is trying to do here) and I was born in 1986. I got a UK passport not because of my dad, who was born in New Zealand, but through his mum, who was born in England. But because he wasn’t naturalized as a UK citizen until March 1987, and therefore wasn’t a citizen when I was born, it seems that after all this rigmarole, Maya may not even have a claim to British citizenship. Unfortunately, I can’t get anyone on the phone to confirm this, so I’m stuck in limbo, feeling like Beetlejuice in the waiting room to hell.

(flossing in her London bus t-shirt, someone give this kid a British passport, photo cred: Kelsey Hart)

This process has coincided with another process I’m going through in therapy, which is rediscovering the disowned British child in me that I put aside in order to assimilate into American culture. It seems my core wound of not feeling like I belong anywhere dates back to when I was four years old and my parents moved us from London to Mill Valley, California, where I experienced such culture shock that my proverbial hard drive was wiped clean and I have no memories from before that age, no memories of London at all. I arrived at Edna Maguire Elementary School with a funny accent and a weird sense of humor, and had trouble making friends. My young life was punctuated by a feeling of social isolation, mistrust of my peers, and trying and failing to feel a sense of belonging. It’s taken me thirty-four years to untangle this.

When I was seven, we moved again. This time to Bolinas, which was another level of culture shock altogether, from moneyed Mill Valley to a hippie surfing village that tore down its signs to keep tourists out. I was part of something called “friendship circle,” which seemed like a great honor until I realized it was for the kids no one liked.

“I didn’t realize it would be so hard for you,” Mom told me recently on the phone.

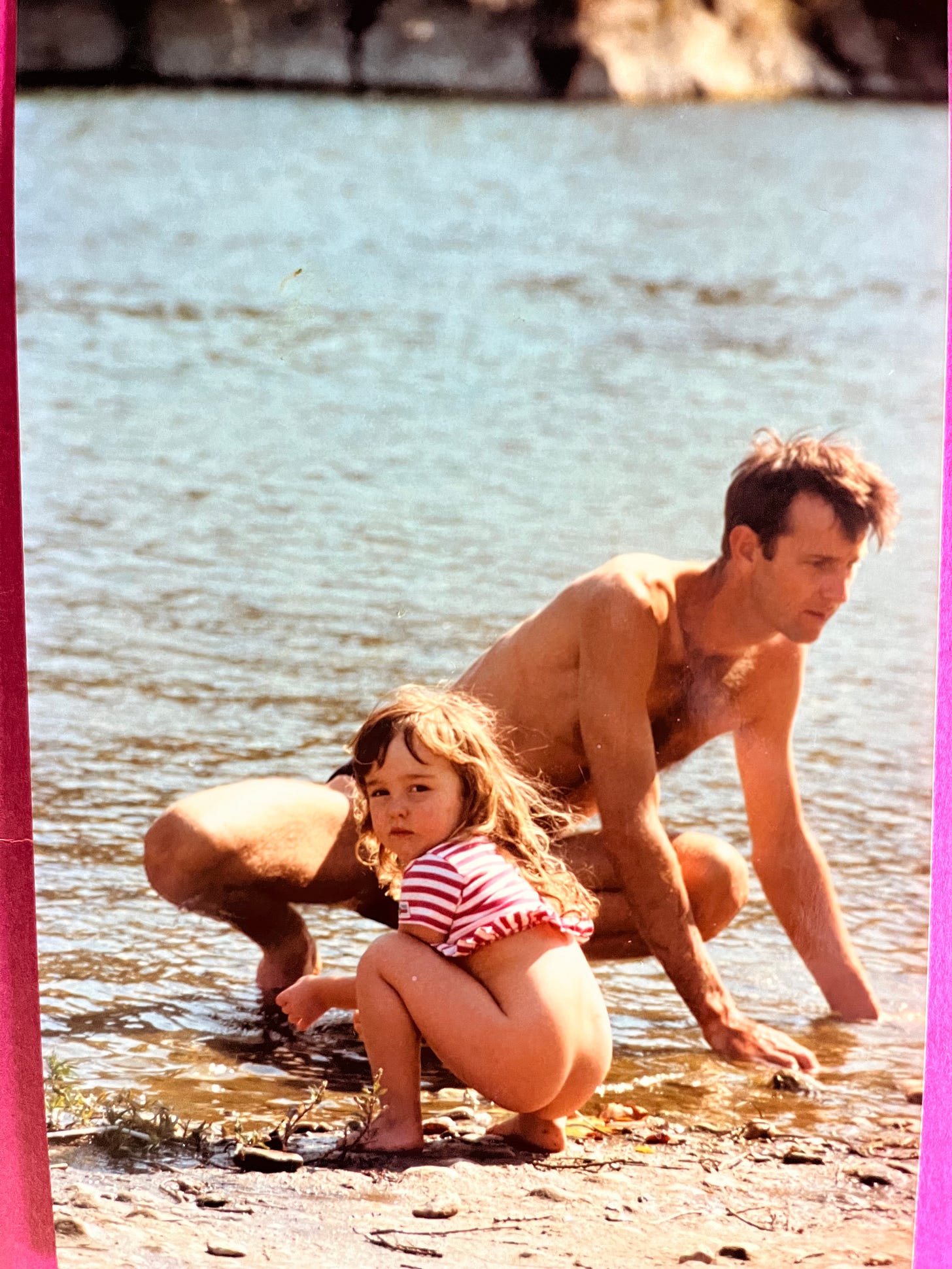

What makes it harder is the dearth of evidence that the little girl I was even existed. Because our house in Hackney was burgled more than once when I was a child and all our VHS tapes were stolen, any home movies of me from that time are gone. There’s one recording, on an old red plastic tape deck. I’m in the background, far away from the device. “Niiiiiiiiick!” I’m calling my dad by his first name, with my little Eastender accent. “I waaaaant summm!”

“I won’t have my daughter talking like that,” my American mom proclaimed, whisking us away from the motherland. It was hard to have a small child in London, dragging a pram on and off the train through soggy, sad weather. Living across the street from a halfway house for drug addicts. Getting burgled multiple times.

Growing up in West Marin, my accent faded over time and I forgot about the outcast British child I was. Then I discovered theatre, and for the first time felt a sense of belonging amongst my peers when I played Demetrius in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in seventh grade. Onstage, I felt free to be as goofy and annoying as I wanted to be, and was rewarded with the miraculous sound of people laughing. Finally there was a place for me to be myself, and a part of my soul was saved.

Then, when I returned to Mill Valley for high school, where I reunited with many of my peers from Edna, I found that little British girl had made some messes I needed to clean up.

(Who me?)

“You called me a witch and said I had a big nose,” said Sandy, who looked at me with wary disdain. We eventually became friends, but there was repair to be done. I found myself making amends for things I didn’t remember, like a drunk who blacks out at a party then goes on an apology tour based on what they’ve been told they did.

“The reason Keith won’t talk to you is because in second grade you gave him a box of crayons to show you his penis,” said Eric, the best friend of a kid who avoided me like a leper for something I couldn’t remember.

It turned out the kids from Edna Maguire thought I was a bully, when what I remembered was my desperate and failed attempts at making friends with them. I guess they didn’t appreciate my mean, pervy sense of humor.

“You’re annoying,” “you’re loud,” “you’re too tall,” was mostly the feedback I received. In response, I cultivated a cool, unflappable persona, a chill NorCal vibe that didn’t feel like me until I’d been playing her for so long I forgot about the rude little British girl inside.

Until she started coming out in medicine journeys, and, if I was lucky, when I stepped onstage.

“I think the reason performing feels so loaded for me is because I feel like I have to prove myself,” I tell Stevie in the kitchen the Monday after performing in a clown show that went so well the audience wanted an encore (not a common request following a clown show). “I felt relieved after the show on Saturday because I’d already proved myself, so I could just relax.”

“So performance is about healing your childhood wound of feeling unloved and unaccepted,” Stevie says, hitting the nail on the head. I look at him, realization dawning, though of course the moment he says it, it seems obvious.

“Was that what you were going to say, or did I jump the gun?” he asks.

“I’m sure I would’ve gotten there eventually.”

(letting out my id with Rebecah Goldstone & The Highland Park Clowns)

Dear Ava…you existed in London. I am looking at a photo right now that I took of you in February 1989 in the kitchen of your house in E9, Hackney. You are eating breakfast with my son, Finn, who was aged 4. You and he had a lot of fun together. You were both clever at creating imaginary worlds. And yes, you had an English accent… (Your dad is an old friend of mine from university days.)

If you ask your mum for my email address, I will send you the photo.